Neurodiversity

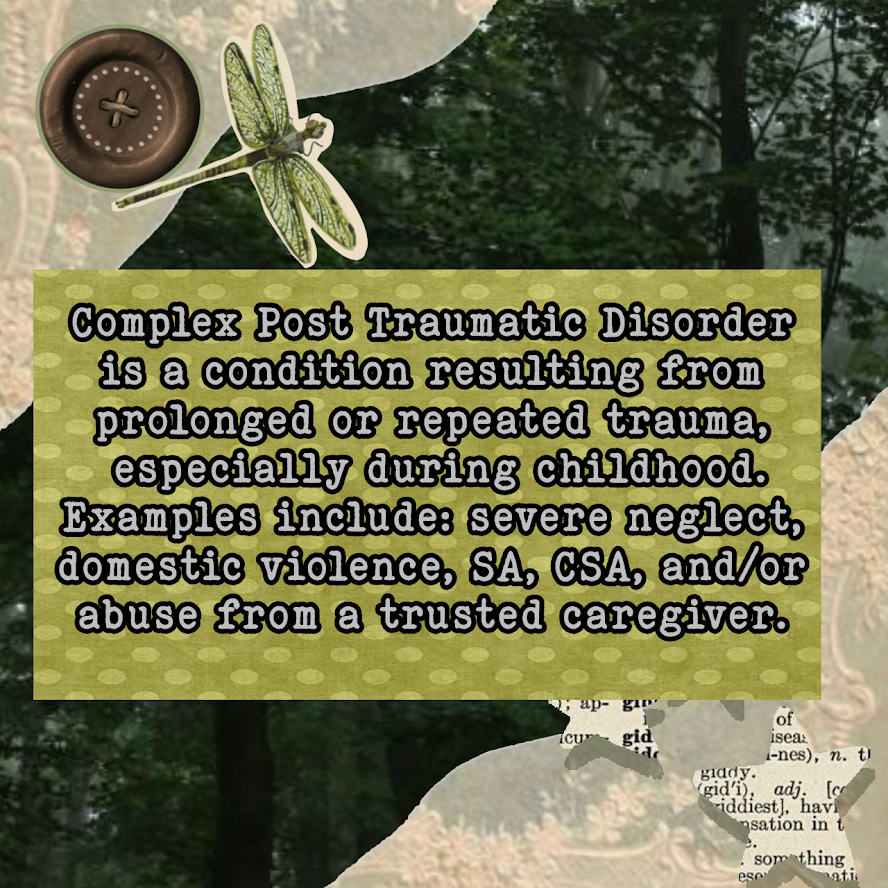

Let's understand different minds, my focus is mostly on CPTSD; ADHD; MDD; sensory processing in general and general neuropsychology (as far as I can find sources to, I'm not a professional). I'll bring articles and books, stay tuned.

Presentation Slides

Blog & article reviews

Transdiagnosis and Dynamic Approach: do labels really matter?

For decades, our understanding of neurodevelopmental conditions like ADHD, autism, and dyslexia has been guided by a simple process: identify a set of symptoms, assign a diagnostic label, and then search for the brain's "broken part" that causes it. But what if this approach is fundamentally warmful, limiting the what is seeking to understand: the unique continuum development of each individual?

This is the central argument of a interessing framework in neuroscience (at least to me). It states that to truly understand why people think and behave differently, even the ones with the same diagnosis, we need to understand how and when those differences emerge overtime, interpreting not as something static that "you have". It is imperative to analyze our journey, the dynamic, changing pathway, environment, etc, just as important as the final word it tries to encapsulate.

Key critiques of the current paradigm include the over-reliance on group averages. When comparing a group means e.g. ADHD vs. Autism [haha, see what i did there?] it obscures important individual developmental differences. What individuals are we talking about? hipo/hypersensory issues? How does the language diverge in each? operational memory? socialization? why not everyone in a group has the deficit, and why the same deficit appears across different groups?

As well as, a person's challenges are not frozen. Our current diagnostic systems, like the DSM or ICD, operate like rigid checklists. Symptoms emerge, evolve, and interact across a lifetime. An early difficulty with hyperactivity can later impact social skills, which may then affect mood. Our static labels can't capture this fluid cascade. They group people into categories based on symptoms observed at a single point in time.

Also, by focusing on the "average" person with a diagnosis, we lose sight of the vast variation within each group. Not everyone with ADHD has the same cognitive profile, and many "core deficits" are found across different diagnoses. This one-size-fits-all model has been a theoretical dead-end.

Many standard cognitive tests are flawed. The same task can measure different skills at different background's, and a weakness in one area (like sound processing) can create the illusion of a problem in another (like verbal memory). This effect means difficulties can ripple through the developing mind, creating complex profiles that don't fit neat categories.

The transdiagnostic approach tries to move away from rigid diagnostic categories and instead study dimensions of behavior and cognition (e.g., inattention, cognitive control) that cut across traditional labels. This allows for a more accurate representation of the population's real-world dynamic.

The paper I'm summaring up brings some proposals like mapping a "typical" developmental trajectory for a brain or behavior measure and then quantifying how a given individual deviates from that trajectory.; building network models of symptoms or behaviors for a single individual using repeated measurements to see how their characteristics influence each other over time.; Hierarchical Bayesian Modelling (HBM); Generative Network Modelling (GNM); etc. You can read more in the actual paper if it interests you.

I quite enjoy this, but as a patient, I do have my fears and critics. A diagnosis is not just a clinical tool; it's social and political. It serves critical purposes. A label like "autistic" or "ADHDer" provides a sense of community, belonging, shared experience, and a shared identity that is often impared by the own disorder.

A diagnosis translates a person's complex, internal struggles into a short-hand that society (schools, employers, governments) is forced to recognize. It's the key that unlocks doors to legally protected adaptations (extra time on tests, flexible work arrangements, etc.). In our current system, no diagnosis often means no access to therapy, medication, or funded support. It is the gateway to necessary services. Im afraid it individualizes struggle and dismantle collective power--- BUUUT! being more resonable about the author's intent and less pessimistic, they are arguing that our current diagnostic map is scientifically inadequate for understanding the territory of human neurodevelopment. Their goal is to create a better map, which could lead to better, more precise, and more equitable tools. In conclusion: The goal should be to build a system where the path to understanding and accommodation is more accessible by using data-driven profiles to argue for a wider range of recognized accommodations. Also, creating a system that validates the experiences of those who fall between diagnostic cracks.

Resources & References

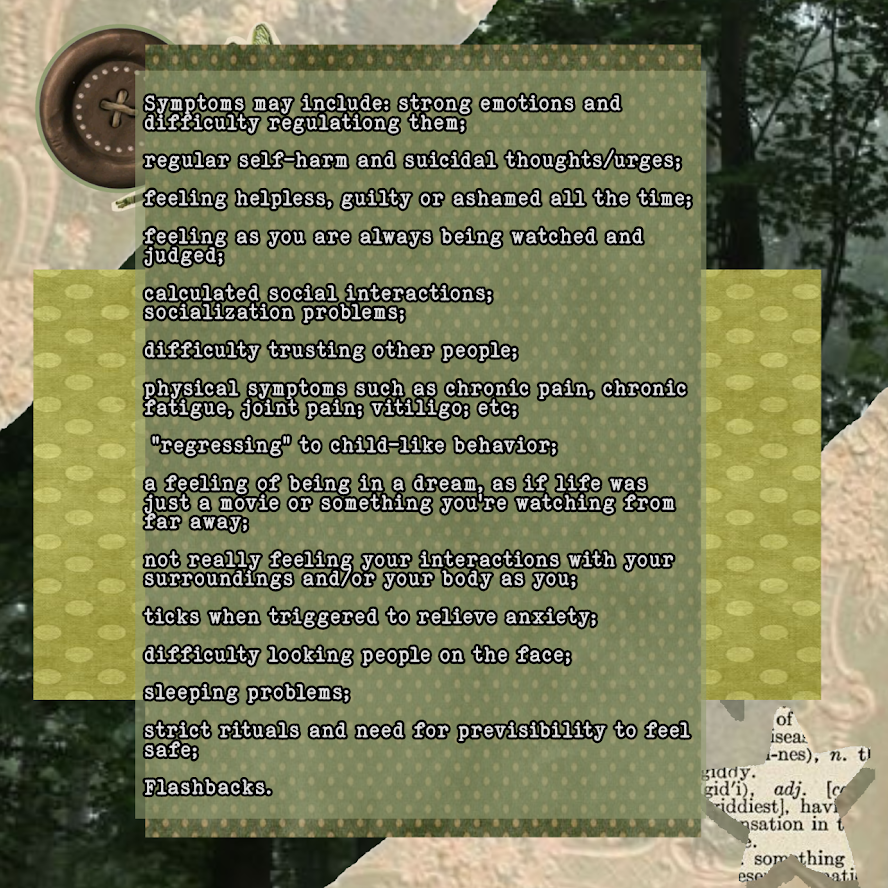

Sources CPTSD slides 1°(take a peek)

Brewin CR. Complex post-traumatic stress disorder: a new diagnosis in ICD-11. BJPsych Advances. 2020;26(3):145-152. doi:10.1192/bja.2019.48

Nestgaard Rød Å, Schmidt C. Complex PTSD: what is the clinical utility of the diagnosis? Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2021 Dec 9;12(1):2002028. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.2002028. PMID: 34912502; PMCID: PMC8667899.

Liu JW, Tan Y, Chen T, Liu W, Qian YT, Ma DL. Post-Traumatic Stress in Vitiligo Patients: A Neglected but Real-Existing Psychological Impairment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022 Mar 5;15:373-382. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S350000. PMID: 35283640; PMCID: PMC8906700.

Transdiagnosis and Dynamic Approach: do labels really matter?

Duncan E. Astle, Dani S. Bassett, Essi Viding,

Understanding divergence: Placing developmental neuroscience in its dynamic context,

Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews,

Volume 157,

2024,

105539,

ISSN 0149-7634,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2024.105539.

(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0149763424000071).